Reading, Analysing and Activating Complex Text

The Orion Semantic

AI system has a vocabulary of about 45,000 words, and about 10,500 phrases. The

first step in analysing a new piece of text is for the machine to read the

text, looking for words or phrases it doesn’t know, and for any words it

doesn’t know in the dictionary definitions of the unknown words or phrases. The

resulting word files are checked by hand if time allows (a dictionary

definition can be very narrow, or missing an obvious definition, including

literal use), and then the word and its meaning structure is created in the

network.

A word can

have several parts of speech (up to 5), if a verb then several types of verb,

then possibly many senses. When reading the text, direct connections are immediately

made so that the word is identified within the grammatical structure . Often,

that is not possible – the POS or senses are reduced, but not reduced to one –

the word is left to be revisited when more information is available – sometimes

the necessary context is a hundred pages away, or in a linked document that

hasn’t been opened yet. As an example, “bar” can be a noun, a verb, a

preposition. As a noun, it can be a simple physical object (an iron bar or a

sand bar), an abstract object (a bar on forever chemicals), a figurative object

(the bar on a high-jump frame – he raised the bar), a collective noun - the Bar

for lawyers collectively). It is obviously important that we don’t get these

things mixed up – our Unconscious Mind does all the work.

In the

machine version, a hierarchical operator is used. If the word has one or more

parts of speech and several senses for the particular POS, a MULTIPARENT2

operator is used. If the POS is a verb, and the verb can take several forms

(Intransitive, Transitive, TransInfinitive, etc. – about a hundred) a

MULTIPARENT3 is used. The operator looks expensive, but only costs one link for

each word in the text.

Figure 1 MULTIPARENT2 Operator

What happens

when the parser cannot decide between senses, or even whether the word is being

used as a noun or a verb. An operator is used which shows a decision is pending,

and an attempt to clear the backlog is made at the end of a paragraph, a

section, a chapter. A similar thing happens when a wordgroup may have been

encountered – is it a wordgroup, in which case which meaning, or a literal use

of the words.

Some examples:

Leave

someone to do something

He left his

wife to pursue his own interests.

He left his wife

to do the washing up while he watched the cricket.

He left his

sons to finish his work when he was gone.

He raised

the bar

He raised

the bar on semiconductor track widths, using far ultraviolet.

He raised

the bar on forever chemicals in the drinking water at the next meeting, saying

the benefits don’t justify the costs.

“Bar” can

mean the figurative use of the bar on a high jump frame, where raising it makes

it harder to jump over, or one can raise (“mention”) a prohibition (a “bar”) at

a meeting.

Figure 2 Senses of Bar as a noun

The point of

the examples is to show that unless you know the meanings of words, there are

many mistakes to be made, especially on a large piece of text describing

something complex.

LLMs were

developed for Search Engines, and didn’t need to know the meanings of words.

Someone found that reasoning was possible on small simple pieces of text, and

used the magical thinking of “In the next release!” to convince people this

minor problem could be solved. Of course it can only be solved by a system that

has a sophisticated knowledge of what words (tens of thousands of different words

and phrases) mean in context, with many of the words not in the text being

read, but “understood”. An LLM is a very crude simulacrum of a knowledgeable human

reader (and a human reader has limits – reading thousand page pieces of text

were not part of the design brief a million years ago, whereas for Semantic AI

they are).

Isn’t English too difficult for a computer to grasp? Won’t you

be back to relying on statistics to decide which sense of a word is meant?

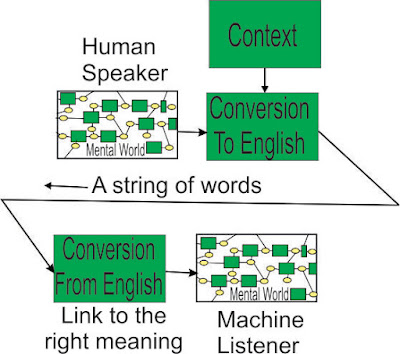

An undirected

network of objects and operators grasps what English is about, and controls the

computer by sending states and values through it, or building new structure or

altering existing structure. As to who does what, it is horses for courses. If

a chatbot can reliably tell a customer how to take out a home loan from a bank,

it is not our turf. If the text runs to hundreds or thousands of pages or

reading requires some knowledge on the part of the reader (the intricacy of a

credit foncier home loan with variable rates can be confusing), it is our turf.

Legislation has domains of criminal law, civil law, military law, where words

have different meanings, some words not in the text become active and some not

(civil law uses “a balance of probabilities” for its standard of proof,

criminal law uses “beyond a reasonable doubt”) and all of it looks different to

specifications for boats or planes or what have you - yes, there will be

statistics, but over a controlled domain. We are already controlling the

context of some senses – (“of a person”, “of a scheduled event”).

The

intention is to handle things which are too complex for a human to grasp at the

big picture level and in fine detail, and yet it is essential to get both

right. The human component is an essential part of solving complex problems, so

this gets a heavy emphasis in the Semantic AI machine’s design – the human’s

emotional states and sometimes irrationality.

Comments

Post a Comment