Telling Lies

Example 1: Robodebt, Australia

A previous Federal Government decided that people on the

dole were freeloading, and $1.7 billion per annum could be reclaimed from them. The

legislation was quite clear that “income averaging” could only apply each

fortnight, whereas to reclaim this amount would require income averaging to apply over a period of six months. There was no possibility of changing

the legislation, but the program was changed anyway. Part of the legislation

said that the government agency should use “best efforts” to obtain payslips.

The programmer was told to leave out anything that was undefined, and the

appeals tribunal was stacked to see things the government’s way. A case was

made to the Solicitor-General, and the practice instantly stopped. Reparations

cost $2.4 billion.

How to avoid this in future? Have a machine read the

legislation and build a working model, using the exact meaning of the words in the

legislation. The social service staff could then have told the programmer that

the program was wrong, short-circuiting the evil-doing.

Example 2: Horizon, UK Post Office

The UK Post Office implemented a new computer system for

sub-post offices. It had a serious bug, in that it would create spurious debts

out of nothing. The consultant assured the Post Office that nothing was wrong,

and the debts were valid. This resulted in about 70 criminal cases per year,

with people who had bought the right to a sub-post office going to jail, no

matter how innocent they proclaimed themselves (private prosecutors were hired,

and were paid a bounty for each person jailed). Each person was told theirs was

the only case of its kind – 13 people suicided to escape the stigma.

What to do? Have a machine read the specification for the

software, and see if it could create a debt from nothing.

Example 3: Boeing 737 MAX MCAS

Boeing needed a new model to compete with the Airbus A320neo

– narrow-body aircraft carrying up to 180 passengers on medium haul flights.

They lengthened the body and fitted bigger engines to an existing model,

calling it 737 MAX. The bigger engines wouldn’t fit under the wings, so they

pushed them forward, which gave the plane a tendency to climb and potentially

stall. To prevent this, they fitted an angle of attack sensor and motorised the

elevators, so the tendency to climb could be countered. If th3ey changed the

flight manual, the pilots would need to be retrained, costing $250,000. Selling

aircraft is a very competitive business, so they didn’t tell the FAA (Federal

Aviation Agency, didn’t change the Flight Manual, and fitted the sensor without

redundancy (commercial aircraft have triple redundancy on their control

systems). The work was given to a company who had never built anything for

aircraft before, and didn’t question the lack of redundancy. The sensor stuck

out from the fuselage, and was vulnerable to bird strikes. When the inevitable happened,

the pilots were faced with a plane that wanted to dive, and a motor that

defeated their best efforts to keep the plane in the sky. The company blamed

the “third world pilots”. After the second crash, the plane was grounded

world-wide, and the reason came out.

How could the deaths of 346 people have been avoided?

The company could obey the regulations, it could use psychological tests to

keep out blackguards from life-critical work, the FAA could enforce the regulations

(the FAA is perennially short-staffed, and often appoints an employee of the aircraft

maker as its inspector), or a machine could be employed to surveil the

operation and report breaches (a sensor was added that was not in the

specification, or a supplier was used with no aircraft experience).

AI is often seen as an aid to doing a job well. These

examples demonstrate the necessity for AI to ensure the job is done well.

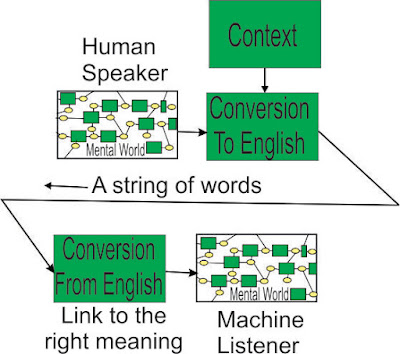

The AI being described here is one that can read and

understand English – Semantic AI.

Comments

Post a Comment