Sending a Message Down This Long Distance Line

The two

sentences

A move by which a piece or pawn directly attacks the

opponent’s king.

If the defending player cannot counter the attack, the king

is checkmated.

work

together. An attack is described in terms of a verb and its subject and object.

Reference is

made in the second sentence to “the attack”, referencing the verb and its

subject and object in the first sentence. The object described by the noun

becomes the object of a relation (“countered”).

To know

whether the attack can be countered requires information from the first

sentence or its instantiation – the type of piece, and the positions on the

board of the piece and the king.

Countering

then becomes

·

Can

the piece be captured? – depends where the defending player’s other pieces are

·

Can

the direct path be blocked (doesn’t work for knights)?

·

Can

the king be moved out of harm’s way?

The

information has to be brought from the description of the attack.

This isn’t

the only possibility.

A move that causes a direct attack by a piece or pawn on the

opponent’s king.

We would

roll up the prepositions so we have an object which exactly matches the verb

equivalent. Should we create the verb equivalent as a simplification, or is

that unnecessary? If we want to activate it, is creating a verb the only way?

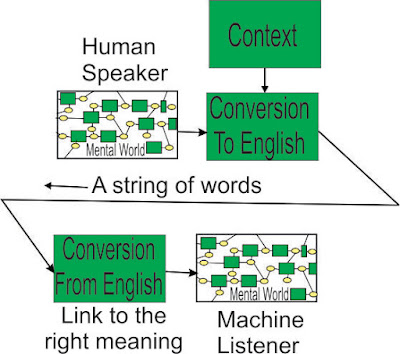

How does the

connection between the object in the two sentences work? – is there only a wire

between the two, and everything has to be rolled up into a message and sent down

the “long distance line”, or is a point of view (POV) transported to the site

of the relation (the noun “attack” functions as a portal to the verb “attacks”

or the noun “attack” in the first sentence).

Real neurons

only have conduction along directed “wires” between them, and yet we are not

aware of that, or it doesn’t impinge on our conscious understanding – it has

been airbrushed out. How? Possibly by doubling up, so everything can appear

undirected?

It is easy

to imagine that we have an operator which connects to the downstream “attack”

on Pin1 and then connects to every important node of the relation (how would we

know that?) in the first sentence. What happens when the verb is clausal, and

its object is a clause or assembly of clauses, and objects in the clause are

defined in a similar way – wouldn’t it explode on us? Or is this the dreaded

Four Pieces Limit?

It sounds

like – yes, it does explode. The text becomes “complex”.

Comments

Post a Comment